Pacing—Rises and Falls: Story Savvy Self-Editing Episode 13

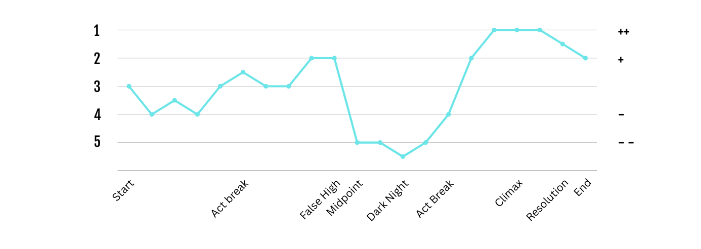

Here is the graph of my personal story shape I promised in episode 13:

As I'd mentioned in the episode, it's roughly a combination of Kurt Vonnegut's 'Man in a Hole' and 'Cinderella' story shapes. I use this combination as I've found it the most universally applicable to genre fiction, particularly romantic fantasy, which is most of what I work on.

I also just want to mention that I only put in enough data to illustrate my point. If you are doing this for all of the chapters in a full-length fantasy novel, there may be more small-scale ups and downs within the overarching arc.

Episode 13 Overview:

Pacing—Rises and Falls

"How can I self-edit for pacing? What is too fast, or too slow? How can I tell and fix it? What if I get feedback that I have pacing problems?"

Want to know how to structure a story plot in editing so it has great pacing? Rebecca shares what makes a good writer great, as she covers what are some good storytelling techniques, how to write a good plot for a story, and how to improve story writing skills!

Today, in the 13th episode of the 52-Week Story Savvy Self-Editing Series, Rebecca Hartwell answers questions from aspiring author Agnes Wolfe (authorsalcove.com), as they discuss your story’s pacing, and how to identify whether your story drags or moves too fast.

Rebecca, a developmental editor who has helped many authors turn their good stories into great ones, offers actionable steps to help you fine-tune your emotional rhythm and keep your readers turning pages, and shares actionable steps to help us know when and how to identify and fix pacing problems. Not only does she provide a way to map emotional highs and lows, but also how to interpret those highs and lows in a way that will best help writers identify when they need to adjust their pacing. Whether you’re on your first edit or tenth, this episode is packed with hands-on advice to help you strengthen your structure and deliver a satisfying reader experience.

In This Episode:

- What is “good pacing” in a story?

- How to spot scenes that drag or rush

- How to use a plus/minus method to help with mapping scenes

- When and how to break the “chapter rules”

- Solving pacing problems

Recommended Resources:

- Story Rise and Fall Shapes [https://bigthink.com/high-culture/vonnegut-shapes/]

- Authors’ Alcove Membership Site – [http://authorsalcove.com]

- Book Giveaway – [http://authorsalcove.org]

See you next week for episode 14: Using Blurbs To Test Story Strength

Episode 13 Transcript:

Self-Editing for Pacing—Rises and Falls

Rebecca: Hello and welcome to the Hart Bound Editing Podcast. This is episode 13 of the weekly Story Savvy series, where we tackle the 52 biggest self-editing topics and tips to help you make your good story great, as an aspiring author asks me, a developmental editor, all of the questions that you have wanted to. We've covered a bunch of different topics in this series so far, including last week's episode on doing research for our stories to avoid factual plot holes or sensitivity issues.

Today we are going to take a look at pacing by discussing the rises and falls of our plots and characters. By the end of the episode, you'll hopefully feel confident defining what makes a story well-paced and in identifying how to spot and fix common pacing issues. Joining me today to ask all of the questions is my friend and co-host, Agnes Wolfe.

Agnes: Hi, I'm an aspiring fantasy author who hopes to release her first middle grade fantasy later this year and also the host and founder of Authors Alcove. I'm here today to tackle the topic of big picture book pacing, which I'm super excited about. So first off, I want to ask what is pacing? What exactly are we checking in our self-editing for this episode?

Rebecca: There are as many definitions of what pacing is as there are authors and editors out there who have an opinion. So here are the ways that I look at pacing collected from various books on craft and my own experiences as a writer and an editor. First of all, it is giving the reader enough time but not too much to cover each thing that happens. So balancing the right amount of brevity or providing details at all times.

Second, it is maintaining a good balance between high-intensity and low intensity moments, which means keeping things interesting often enough and in the right places, but also letting the reader process and take a breath often enough in the right places. Third, it is using scene and chapter breaks to present the story in correctly lengthed, bite-sized pieces. Fourth, it is using variety in the type, emotion, intensity, direction, change type, and outcome of scenes to avoid burnout or boredom from repetition in the reader.

And then I forgot what number I'm up to, I think it’s fifth, is making sure that each scene in the story always has momentum moving towards or away from something meaningful and avoiding describing things passively without, or, that are happening, without direction.

Angie: So how can we tell when the pacing or emotional rhythm or whatever else you want to call it is off?

Rebecca: That is really the overarching question for this episode. So let's just plow ahead for the moment and hopefully that will feel answered by the end of the episode.

Agnes: Okay, so how can we tell if we are describing something too much or too little?

Rebecca: We'll definitely go into this more later in the series, like at the line level, but at this stage let's go ahead and take a look at the very big picture for this. So on a scale of one to however many you want to work with, how vital is an aspect that you are looking at or a character or event or etc. to the main plots? The amount of description that that element or aspect or whatever gets should match that number.

So your protagonist, hopefully, is going to rank number one on importance for character importance to the plot, or at least it should. So they get the most description without it feeling like it's too much, though still, you know, using good judgment is a good call to not go overboard on describing them. However, a character with minimal or no speaking lines or who only shows up in one scene or could be replaced by just about any other character should be scoring very low on whatever metric you're using to rank this, and therefore should be getting a similarly reduced amount of description or page time or however you want to count that.

Genre is also going to have a lot of influence on this topic as well, so knowing what your readers expect as far as how immersively detailed or how, you know, sparsely action-driven the story is is very important. That's why we cover genre and audience so early on. The last point that I want to touch on here is that you can also just look at the length of the chapter that you are worried about being over-described or under-described if you are confident that you're splitting your chapters well, which we'll touch on a little bit later.

If it's too long, look at where you may have gotten too much in the zone with describing things in very, very deep detail more than is needed and how you could trim that down. If it's too short for your ideal chapter length or scene length, then look at how you could add more meat to the scene with more things happening using more scenes to describe the setting or events and that kind of stuff to bring it up to that ideal length. So you can kind of judge.

It's not foolproof at this point, but if you really feel like your scenes are more or less consistent, you have outliers, those are often hints that it's underwritten or overwritten.

Agnes: So, you know, this is one of those things where I know, because I actually like when people break this, but where you have to know the rule before you can break it. So I'm going to bring this up, but you mentioned chapters earlier.

What is a matter? Should we break chapters where things are wrapped up between scenes or right before climaxes, like mini cliffhangers?

So that's the overarching questions, but I'm going to preface this with I love the absurd, but it's one of those things where it has to be the right book to be able to break this and have it. And there's certain authors who I absolutely adore who totally break this, and they'll have like one sentence. Jasper Ford is one of them.

But like some of my favorite authors do this, but this is also one of those that I know that you have to know the rule and do it well before you can break it. So let's just start off with should we break chapters where things are wrapped up between scenes, or right before? What are the best rules about that?

Rebecca: Yes, so I totally agree for starters that if you have a rule established, then when you break it and you do so intentionally, it can be great, but you have to have the rule established first. So bite-size is basically what it sounds like.

It's incredibly rare to find books that aren't split into chapters of some length of some kind for a very good reason that we all know that books are easier and more fun to consume when they are parted down like that. My favorite analogy for bite-size chapter lengths is that many, many more people, including myself, would rather sit down and eat a whole bag of potato chips in one sitting than would happily eat one giant potato in one sitting. So that's basically what we're doing with our whole book is we're breaking it down into literally consumable smaller portions.

However, there is a happy middle ground in this. You don't want to have a hundred one-page chapters for the most part. Your genre will often dictate chapter length a little bit, such as high fantasy being far more accepting of longer chapters than, let's say, contemporary romance.

But the rule of thumb for genre fiction, which is what we're mostly talking about editing in this series, is 1.5 thousand to 2.5 thousand words per chapter. You can't really go wrong in any genre if you're aiming for that middle ground. And even in high fantasy, which allows that longest, I strongly suggest keeping your chapters under 5,000 words whenever possible.

As for where to split chapters, there are two different right answers as far as I'm concerned as an editor, which are the two that you mentioned actually. So to go into detail on those, option one basically treats scenes or a grouped set of scenes that go together as chapters, basically, synonymous with chapters for the most part. Both are containing a single major event for the story, the lead-up to it, and the fallout.

And it's this nice little encapsulation around the main event of that scene and or chapter. Option two is what you'd mentioned where you choose to use those mini cliffhangers to aid in the momentum of your story, carefully splitting your chapters right where the tension is highest in the middle of a scene, right before the climax of that scene is revealed. And then you'll have your scene beginnings and ends in the middle of a chapter, more or less.

You can never really go wrong with the first option, but I do have a slight warning with the cliffhanger version. If you overuse it, it can feel cheap, frustrating, and like you're trying too hard to manipulate the reader into reading on in a way that's, like I said, more manipulative than good story craft. I will also just add that using cliffhanger chapter breaks are more likely to be a good choice and received well by your reader around the global climax. If you really want to do that, do it in that part of the story.

Agnes: So one of the things that I noticed that you're talking a lot about is, because you said, if this, then that, like we have to know our audience is essential. And I think it goes back to like, I really like when people do the breaking, but it has to be the books that are absurd.

So like any serious book cannot get away with it. So their target audience is people who enjoy the absurd. I love nonsense.

I love whatever, which is why I love Jasper Ford for example. But speaking back to like pacing, I know as a reader, some of the biggest mistakes I see writers do is they have things either low for too long or high for too long. If it is high for too long, I will set it aside.

Like I just can't handle, I've read some and if it's too emotional for too long, I have to set it aside. I can't handle it. And then if it's too low, I tend to get bored and I forget about the book.

And I set it aside again, and just forget to pick it back up. So how do I know if I have too many high intensities and too many low intensity ones in a row, as far as scenes and stuff?

Rebecca: For what it's worth, I think this is also the most common issue that I see as an editor is either burnout, which is too many high intensity, or boredom, which is too many low intensity. So my personal recommendation for tackling this in the self-editing is I suggest spreadsheeting it.

And I know not everyone is a spreadsheet person like I am, but it can be very helpful and it doesn't matter if this is on a computer, if you're doing this on a lined notebook, just having that sort of structure can be very helpful. So make a list of each chapter name, or if you want each scene name if you haven't decided on your chapters yet. Then, next to each of those entries, mark how high intensity or low intensity you feel it is.

You can pretty much do this any way you want to, but I will often use a plus or minus sign, or if it's extreme, a plus plus or a minus minus, just to kind of have a very quick visual gauge for where that scene is on an emotional scale. Once you have that list, just look for clusters. If you have a run of lows together, a run of minus signs together, then look at where you could bring the interest or the tension up, or make more things go wrong, whatever you want to do to kind of break up that run of lows.

If you have a run of highs together, a bunch of plus signs all in a row, then look at where you could let your protagonist, and therefore the reader, take a breath and process whatever high tension things have been happening on either side of that.

Agnes: I love that, because that was something that, I don't know, I loved what you just suggested about the plus plus minus minus plus minus, and you don't even have to do a spreadsheet, really. You can just put at the beginning of your chapter or beginning of your scene, depending on how, because some people break it up with scenes, some people break it up with chapters, whatever.

You could just do that even right in front of that, as the name, and then you just kind of scroll through. I really like that. That's not something I thought of, and I think it's going to help me in my edits now. Thank you so much.

Rebecca: Excellent. It's definitely a simplified version of something that Story Grid recommends, and they're called Story Grid because they love spreadsheets, and they do all kinds of grids like this.

Agnes: See, I did Save the Cat. That is what I read, and I keep meaning to get Story Grid, and I actually got it on my Kindle, but I think I need to buy just a hard copy, because I don't think I'm going to remember to read it on Kindle, because ever since you recommended it, I keep thinking, and you recommended it to me over a year ago when I interviewed you for the podcast, and I've had it on Kindle ever since, and I keep thinking, I want to read this one too, but I always pick up my Save the Cat, because it's the one I have in hard copy when I go to reference.

Rebecca: Story Grid isn't a Bible. It's not perfect as a resource, but boy, it has some gems in there, and reading through it, you can just make a mental note like, oh, that little thing, that's a great idea. I'm stealing that. So that's why I recommend it. It's not like the be-all, end-all, but it's got a lot of great nuggets that might fit any individual author.

Agnes: And I think that's true about anything, like even having your developmental editor. I would probably change like 90, maybe 80 to 90 percent of what you said.

I'm like, yes, she is so right. I need to change this, but there is that 10. I bet it's closer to 10, 10 percent where I'm like, no, no, I'm not listening.

Rebecca: Honestly, those numbers are better than normal. So…

Agnes: I haven't fully done the editing. I've been kind of setting it aside because I've been daydreaming about the other books, which, by the way, it's come up to five now. I know I had said it was three, four, and then I realized that second or that third, fourth book, it's now, it's turned into two books. So I'm like, wait, I have two storylines going here. But anyway.

Yeah. All right. So I'm loving this series, by the way.

Okay. Are there patterns we should be looking for when we are analyzing our pacing and emotional rhythm? Like I'm assuming the highs should progressively get more intense as we go to the climax.

Rebecca: This could be a whole episode on its own. So I will see how briefly I can answer this, but probably not that briefly. Okay. So first of all, you never have to have a perfect alternating between these highs and lows.

It doesn't have to be plus minus, plus minus, plus minus. That by itself is going to become a repetitive, frustrating, boring pattern. The exception here is that having a run of lows in the dark night of your story, so right after that midpoint drop for most story structures, is acceptable.

And having, you know, three or four highs in the climax is also acceptable. So that's one of those patterns that you can look for, is if you're going to have a run of lows, it's here. If you're going to have a run of highs, it's over here towards the end of the story.

I also love that you brought up that progressive aspect, because it is so important. And that's why I recommend having more than just plus and minus, having an extreme plus or an extreme minus in that measuring mix that you're using. It is really important that the highest high is the climax, and that the lowest lows are in that dark night or that midpoint drop. That kind of stuff.

So here's a really, really rough explanation of the two most popular patterns for this pattern that you're asking me to explain here, that you can watch for, both of which are based on Kurt Vonnegut's story shapes, which I'll link in the description for this episode. My go-to story shape is roughly a combination of two of them, so man in a hole and the Cinderella shapes.

So first, picture a graph with one at the very top, at the highest high, the plus plus plus, and then you have five at the bottom, which is the most negative scene or moment in the book. Right where the story starts, and I'm sorry if I get my right and left mixed up here, I'm not sure how this is going to look to folks watching the YouTube video, so bear with me, but right where the story starts, or perhaps the day before if you're starting the story as late as possible as I generally recommend, is going to be a three. It's going to be in the middle.

That's the neutral baseline. The first major event is then going to drop down to a four as the protagonist is thrown off balance and is forced to step deeper into the events of the story. Right after the first act breaks, so around the one-quarter mark, things are going to pick back up to a three, back to this neutral point as they regain some new sense of stability, likely because they've crossed the threshold into a new world of some sort.

Things keep building up to a false high of a two over the second quadrant, and you want them to hit that sort of false high before it drops all the way down to a four or a five at that midpoint shift, that midpoint drop that we've talked about in previous episodes. Through the dark night, it dips down to a true five, a true bottom of the bottom for your genre, for the story that you are telling if it didn't land there immediately with the midpoint drop, and then slowly crawls its way back up to a three as the protagonist goes through their needed internal changes, comes up with a new plan, better understands the force of antagonism, whatever that dark night arc is for them. Then the climax around the last act break, maybe into the last act, wherever you're placing that for your story, peaks at the one.

And it's expected that that one is going to be, you know, that's what makes it the climax. If the climax isn't the one in your story, it's not going to land right with the reader. And then after that, it's expected that it might ease back off into a two in the resolution, so between the climax and the end, as things get metabolized and the adrenaline comes back down.

But you'll notice that you started at a three, and you want to end at a two, especially if it's a prescriptive story, which most genre fiction is, so that you're showing that the story was worth it, because the starting point is a point worse off than the ending point, which means the story was worth telling, it was worth going through for the protagonist, all of that kind of stuff, showing that the new normal is better than the old normal was. So you can do this on a graph, you can do this on pen and paper, you can just do this in your head, whatever you want to do for that.

But the caveat that I want to add to this is that this, I've given this false impression that it's this nice, smooth line. It's not. I highly recommend when you're charting them, yeah, when you're charting it scene by scene, the whole like two steps forward, one step back is a great idea, and that can be two steps back, one step forward when that line is going down, and having that variety within that overarching arc is good story craft.

Agnes: And I think even just thinking of a mountain, because a mountain isn't like this, a mountain is like, and so like just thinking of a mountain, and I'm going to completely be honest here, so I do struggle with ADHD, a lot, and as soon as you said Kurt Vonnegut, I cannot say his name, he's like one of my favorite authors, and so like I literally like zoned out, and I'm so glad I get to watch this video again, because I'm like, I start thinking Breakfast of Champions, I remember something when I was, you know, like I started telling myself, I'm like, oh wait, what did she say? So yes, he is one of my all-time favorites, and it's because I have so many memories of reading his books, and yeah, but I like a little bit of absurdity.

So anyway, back to the questions. So one of the things that I know that I felt that I was doing in the first couple of my chapters, and like my first like, my first full draft, the first like 10 chapters really, is that I tend to plod along. What are things we should do to be sure that we are not boring our reader? And I still feel like I need to work on that with my first couple chapters, but like, that was something that I know I really struggled along, especially in the beginning of my book.

Rebecca: That is, that is a common issue, so don't feel too bad about this. The answer to this is basically the last two bullet points that I had in my very first answer for this episode. So, first and foremost, make sure that each scene in the story always has momentum through two checks that you can do on this.

First, make sure that something meaningful changes in the scene, which affects how or in what direction the story moves forward. And I'm going to keep saying this, how big that change needs to be, what kind of change that needs to be, is all going to depend on your genre, what kind of story you're telling, and where you are in the story. So just look for some kind of change.

Second, make sure the scene has something pulling the protagonist forward that they want, or pushing them forward which they are avoiding. So, this can be, oh I want to, you know, steal the or I'm running away from a bad family situation. There should be one of those pulling that story forward in every scene and that will really help with momentum, rather than just observing, oh they're doing this and now they're doing this and they're just living their life.

So, moving on to other bullet points there, having variety in scene type, or having variety of any kind, can help a lot with a plodding book, chapters, or scene, or whatever measurement you're looking at, including a variety in scene type, so traveling, or chatting over a meal, or fighting, or whatever else. You don't want to have multiple sitting and talking at a meal in a row kind of thing. You can have variety in tone, so serious, playful, stressed, chaotic, rigidly ordered, etc.

You can have variety in emotion, or intensity, which the last two questions kind of covered, so happy, scared, yearning, angry, curious, etc. You can have a variety in direction, so whether the protagonist is getting help and moving closer to their goal, or encountering hurdles, and moving further away from it, and encountering the force of antagonism. You can have variety in what the core change type of the scene is, so it moves closer to or away from freedom, or closer to justice, or away from enlightenment, stuff like that.

I hope that makes sense. So, you can also do, lastly, you can do variety in the outcome of a scene, whether the protagonist essentially won in that scene, or lost, and what that win or loss was.

Agnes: One thing that has occurred to me, because I'm a beta reader, I read all different genres, I'll do for beta reading, as long as it's something that I'd be interested in, is that when we're getting feedback from beta readers, so like I feel a little different, so when I'm saying something to a beta reader, I feel like I'm going all over the place.

I don't think that it's like set in stone, I think it's more of a preference thing. So like I'm going to take what you say about like if something feels too rushed, differently than I am going to from a beta reader. So what if we get notes back from beta readers saying our book is too slow or too rushed, how can we gauge whether it's a preferential thing, or whether it's something that we, or what we should actually look for? This is a great question and pretty applicable to all beta reader feedback, so hopefully if listeners hear this and they have similar issues, this will still be helpful.

Rebecca: First and foremost, I recommend asking for further details from your feedback reader, if that's remotely possible. Just like, hey, can you jump on a call, can we talk about this for 10 minutes? But there are a few common things that you can look for if you specifically get beta feedback on your pacing issues. So, if the whole book is slow, according to your beta reader, that can often be a lack of strong present or impactful goals or motives propelling the story along its path, in which case you should look at taking those up a notch as much as you can.

It could be a lack of tension and conflict. When things are too easy, or too coincidental, or too lucky like we've talked about in episode 11, that can definitely come across as slow pacing. In that case, I suggest revisiting episode 11 and that brainstorming exercise that I about reducing that plot armor impression to casual readers.

It might also be too much description of things that don't really matter to the plot or protagonist's arc, which is often called fluff or shoe leather or purple prose or overwriting or the like. In this instance, I recommend either setting the issue aside until we get to the episode in this series that will cover this much later, or just doing what you can now to really go through and make sure that there is an emotional plot relevant or meaningful character relevant reason to each paragraph as much as you can. Lastly, it can be a general lack of interesting aspects to the book.

So, if you think that's the case, if your beta reader says that's the case, I suggest doing a lot of brainstorming around how you could push any and every aspect of the book to be more unique or emotionally charged or innovative and just see how you can move those different parts of the book in a more interesting or innovative direction.

On the other side of that, if you get feedback that the book is too fast from your beta reader, then here's what I suggest. First and foremost, it could be that you are simply trying to do too much in one book. If you think that that might be the case, if that's what your beta reader is saying, I suggest revisiting episode six of this series on possibly splitting that story into multiple books so that they all have more room to breathe and assess if that might be the right answer for you now that you're getting that feedback.

Second on if it's too fast, you can check to see if you have gone too much in the direction of making everything too interesting at all time and aren't letting the protagonist or reader breathe, take a breath. In that case, I suggest that you make a list of the big moments in the story and make sure that they are properly processed by the protagonist and other characters in between them.

Specifically, you want that processing to happen as soon as it makes sense to do so after the big event and to do so in enough depth and detail that it really supports whatever choices or internal changes you want to come out of it for that protagonist arc.

Third and last on this, which is basically another approach to that same issue of not letting the reader breathe, see what you could add in to space out those high-intensity or fast-paced parts. This could be disadvantaging the protagonist in some further way so that it's harder for them to reach each next step. It could be a subplot designed to complicate the path to the climax, or a bunch of other options where you're just adding more content to space out that high-intensity burnout. And if you do this route, I do recommend that you, again, go back to the episode where we discussed possibly splitting your stories and make sure that you don't now need to do that, so that you have two better-paced books.

Agnes: So, I know we need to wrap up, so I just want to ask one last question. I feel like it's kind of restating what we've already stated. I loved the thing about the plus and minus, I love the going up to the one, but what are some actionable steps we can take to check the pacing in our own work?

Rebecca: I've got a couple of actionable exercises for this.

So, if you make a list of your major moments for the internal and external plot, if you're playing with both, and rate them by how big they are, or are likely to seem to the reader, are each of those big moments getting an appropriate and proportionate amount of addressing? Or is that off in either direction? So too little addressing, too little description for the big things, or too much description and addressing for little things. Just make a note where those need to be adjusted, and in what direction. Then later on you can go in and actually make those changes.

The second exercise is, do you have a nice mix of emotional rises and falls, or is your story just plodding along like we were talking about earlier? Do you have enough emotional rises or emotional falls, and do you have too many in one area or another? Again, we've already talked about this. So if you spot an issue, an area of issues around this, could you fix it by rearranging the order of scenes that you already have written and tweaking them to make sense in that order, or by changing the tone or outcome of a scene? So rather than adding or subtracting, can you just use what you already have and tweak it to make that fit better?

Exercise three is, are the events in each chapter motivated, at least in some small way, by moving towards or away from some global goal or motive? Is your protagonist noticeably closer or further away from their goal, need, or genre value such as love or enlightenment than they were at the beginning of that scene or chapter? If your answer is no to either of those questions, what moment or change could you add to that scene to keep up that momentum and interest?

We will definitely go into this one a lot more heavily in a later series when we get down into the scene-by-scene sort of structure, but looking at it at this point, if you're worried about your pacing, can still be worth it.

Agnes: Well, thank you so much. I found this particular episode one of my favorites that we've done so far, and I think it's because you gave me some actionable steps that I'm like, okay, because I know that I have some pacing issues, but I also like, okay, I can go by what you said when you read it, but I want to be able to look at it once I'm all finished, because I might be adding, subtracting, and then I might have a totally different type of pacing issue once I've corrected the pacing issues that you suggested. So this has been such an amazing one. Thank you so much. I really appreciate it.

Rebecca: Excellent. I'm glad to hear it, and you are quite welcome.

Next week, we will go over using a very rough blurb to check the very biggest overview of what shape our story is in. For now, I really want to thank all of our listeners and everyone following along with this series. We would really appreciate it if you would help us out by liking and subscribing to the Hart Bound Editing Podcast and the Authors' Alcove Podcast, where you can find lots more content for fantasy authors and readers beyond this joint series.

And if you haven't already, I encourage you to check out the Authors' Alcove community on Patreon or their new membership site at authorsalcove.com. Thank you all so much.

Agnes: Thank you. Bye.

Rebecca: Thank you so much for listening to the Hart Bound Editing Podcast. I look forward to bringing you more content to help you make your good story great so it can change lives and change your world. Follow along to hear more or visit my website linked in the description to learn how I can help you and your story to flourish.

See you next time!